This section of the White Paper deals with the marketplace for laboratory services. For brevity and clarity, I will address five components: 1) independent commercial laboratories; 2) hospital-based laboratories; 3) esoteric, reference, and specialty testing laboratories; 4) anatomic pathology lab- oratories; and 5) diagnostics manufacturers and suppliers. These groups represent the basic divisions within the …

Competitive Dynamics In the Laboratory Testing Marketplace Read More »

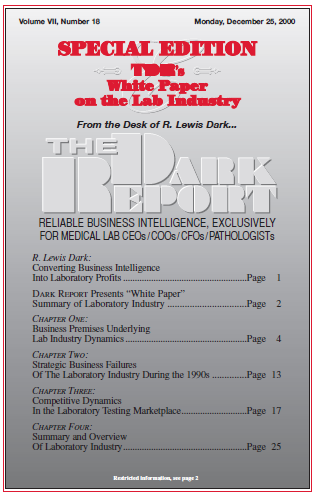

To access this post, you must purchase The Dark Report.