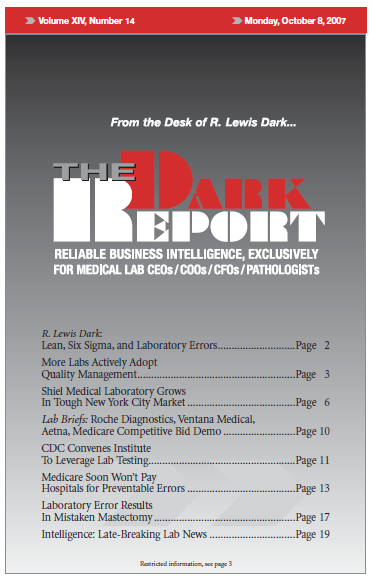

CEO SUMMARY: In New York, because of a laboratory error and wrong diagnosis, a woman underwent a needless double mastectomy. In reporting the case, New York newspapers discovered another case of lab error and both women are suing the labs involved. Each case is a reminder that the public and state healthcare regulators are becoming […]

To access this post, you must purchase The Dark Report.