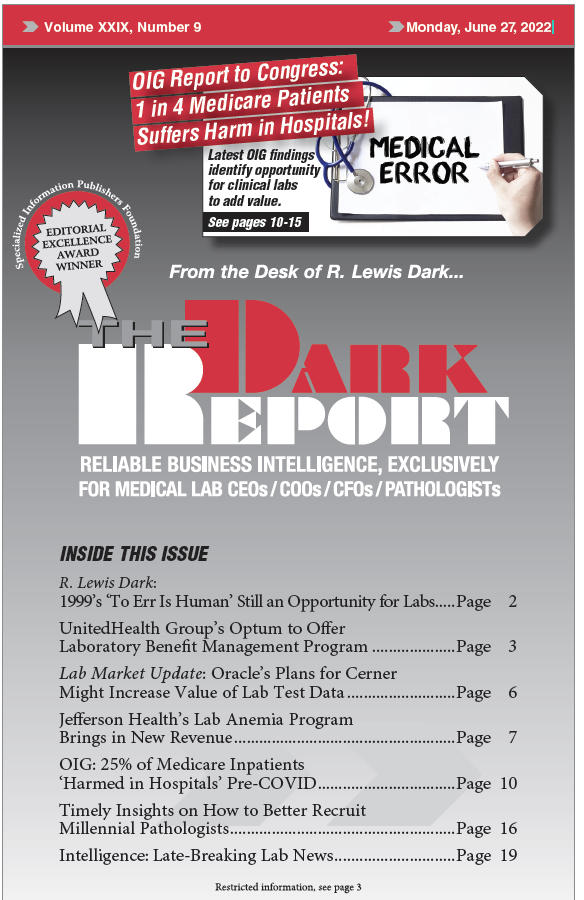

CEO SUMMARY: This year’s report to Congress on patient harm in hospitals—prepared by the Office of the Inspector General (OIG)—determined that one in four Medicare beneficiaries suffered harm while an inpatient in a hospital. The report garnered little attention outside the healthcare press. Moreover, the OIG’s findings about the incidence of patient harm in hospitals …

OIG: 25% of Medicare Inpatients ‘Harmed in Hospitals’ Pre-COVID Read More »

To access this post, you must purchase The Dark Report.