CEO SUMMARY: In eastern Washington State, InCyte Pathology is developing a strategy that may well be repeated many times over in the coming years. As older pathologists who run smaller groups look to retire, they will consider selling their group practices to larger entities interested in forming regional pathology groups. These larger groups will consolidate …

Smaller Pathology Groups Explore Consolidation Read More »

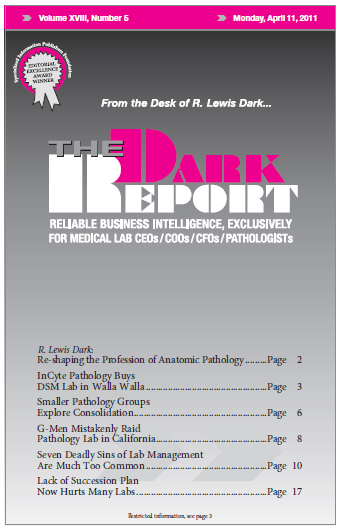

To access this post, you must purchase The Dark Report.