DURING HER ADDRESS TO THE ANNUAL MEETING of the American Clinical Laboratory Association meeting in March, Rep. Diana DeGette (D-Colo.) explained why she and others in Congress had developed the Diagnostic Accuracy and Innovation Act (DAIA), a discussion draft that would give the FDA authority to regulate laboratory developed and in vitro diagnostic tests. At …

FDA Issues Response to Draft Legislation to Regulate LDTs Read More »

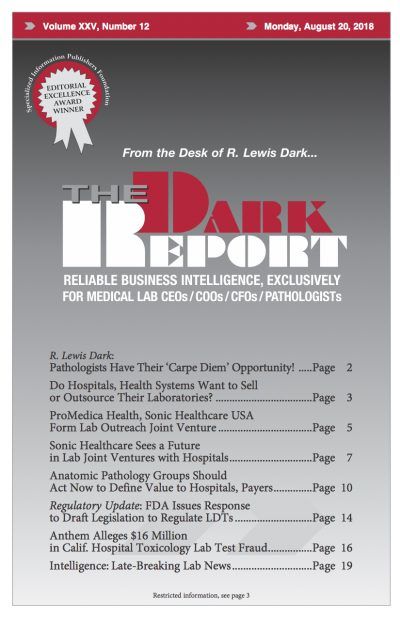

To access this post, you must purchase The Dark Report.