CEO SUMMARY: When the American Clinical Laboratory Association filed its lawsuit Dec. 11 against the Secretary of Health and Human Services, one of its main claims is that HHS collected payment data on the clinical laboratory testing business in a manner that was deeply flawed. HHS then used that flawed data to set payment rates …

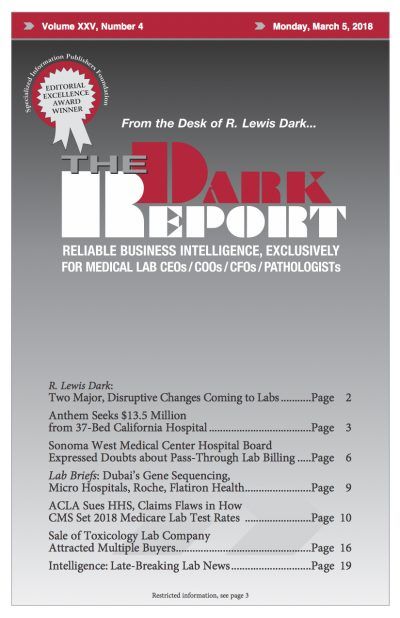

ACLA Sues HHS, Claims Flaws In How CMS Set 2018 Rates Read More »

To access this post, you must purchase The Dark Report.