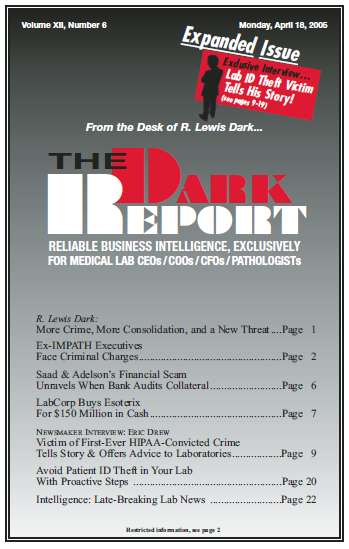

CEO SUMMARY: Identity theft is one of America’s fastest- growing crimes. Not only that, it is simple to commit and can be done by anyone. Few laboratories and pathology group practices are prepared to deal with the crime of patient identity theft. Labs should proactively move to implement protections against patient identity theft and raise […]

To access this post, you must purchase The Dark Report.